Serious critiques of meta-analysis and effect size: researchED 2018

By Rob Coe Since I became a researcher in the late 1990s, I have been an advocate of using effect size and meta-analysis for summarising and...

Login | Support | Contact us

Professor Robert Coe : Sep 6, 2018 1:21:00 PM

4 min read

In part 1 of this series of blog posts, I set out some of the recent criticisms that have been made by researchers such as Wiliam, Simpson and Slavin about the use of effect sizes to compare the impact of different interventions and the resulting problems in combining them in meta-analysis.

If effect sizes are so confounded with methodological aspects of the studies from which they arise – and in ways that are seldom, and perhaps can never be, unpicked from those studies – should we trust them as indicators of the effect that an intervention is likely to have in our school or classroom?

If we discount all the ‘evidence’ from meta- and meta-meta-analysis, what are we left with? Is this a crisis for evidence-based (or even evidence-informed) practice?

First of all, I think we do not need to panic about these critiques. Most of the points they make about factors that can affect effect sizes are well known to meta-analysts and have been written about and considered for many years.

For example, even my own brief 2002 primer on ‘What effect size is and why it is important’ draws explicit attention to the potential problems of range restriction, non-normal distributions and measurement reliability. I gave further advice on cautions and recommended practices in using and interpreting effect sizes in a 2004 chapter But What Does It Mean? The use of effect sizes in educational research.

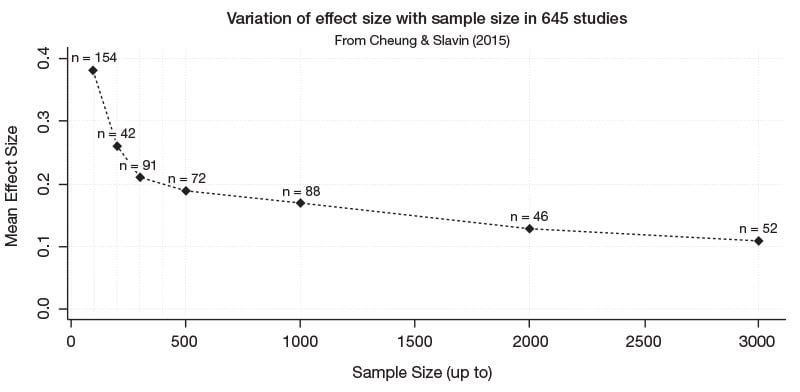

Cheung and Slavin’s 2015 paper drew particular attention to the relationship between sample size and effect size, among other methodological features. A graph showing this relationship for the 645 studies they analysed illustrates this dramatically:

But the key point is that the people drawing attention to these caveats are not saying ‘Don’t do meta-analysis’, but ‘Do it more carefully’.

Second, I do think we need to take the critiques seriously. If these confounds are inextricably and endemically woven into all our current evidence base, and if their distortion of effect sizes is non-random and substantial, then it will make a difference to the conclusions we draw.

Potentially, we could be wrong about some of the claims and conclusions we have made. It certainly is clear that methodological features of a study can make a big difference to the effect size it finds.

What is less clear (to me at least) is how much difference they actually make in real reviews. That the worst possible extreme case would give the wrong answer may not be a good guide to what we typically experience. A sensible response to these important criticisms would seem to me to be to investigate further how big a problem this is in actual meta-analyses, and to what extent it can be corrected for or mitigated.

For example, Cheung and Slavin’s empirical review of these confounds in real studies alerts meta-analysts to look at and control for features such as sample size and independence of outcome measures when they combine effect sizes.

Partly with a view to formulating this research agenda, we are hosting a seminar in Durham on 4 June 2019 at which Dylan Wiliam, Adrian Simpson and Larry Hedges (among others to be confirmed) will debate these issues.

Third, we need to pay careful attention to the limits of what research can and cannot tell us about practice. Does a +7-months impact for ‘metacognition and self-regulation’ in the EEF Toolkit mean that if you pick any intervention with the word metacognitive in its name and do more-or-less what it tells you to in your school that your pupils will leap seven months ahead of where they would have been?

No, of course not; much more likely is that it will make no difference at all. All it tells us is that in the studies that have been done, and reviewed, so far (with all their limitations), interventions that have contained a clear metacognitive component have often been more effective than many other kinds, taken on average.

Or if you are weighing up competing arguments about how to narrow the attainment gap in your school, between giving additional support to low attainers through separate, smaller classes, or by providing additional in-class teaching assistants, or by offering targeted one-to-one tuition, then you probably should know about and consider the evidence about these three types of intervention.

And, crucially for me, the kind of discussion you are likely to have with a school leader who does understand that evidence is very different from the discussion with a leader who bases decisions on their personal experience and gut feeling.

Ultimately, the best evidence we currently have may well be wrong; it is certainly likely to change.

The key point about science is that it doesn’t guarantee you will be right; in fact, you almost certainly won’t be. What science does provide is a process for becoming gradually more right, on average.

That is why the scientific approach to identifying best practices is the best long-term bet.

If the extreme form of the criticisms of effect sizes and systematic review are right and they really are worse than useless, then the price we must pay is very high.

Imagine a teacher or school leader asks you a question like: ‘We want to develop classroom practices, but are not sure whether to focus on explicit instruction or learning styles?’ or ‘We have the opportunity to invest, but not sure whether to prioritise reducing class size or CPD?’ what would you say?

Your answer might be:

(a) Education research evidence is not currently up to answering those questions: we don’t really know;

(b) My opinion is X;

(c) The best available educational research evidence says Y

If you feel we need to do better than either (a) or (b) then I challenge you to give an answer that does not depend on some kind of combining of effect sizes.

If you think you are using some way of doing this that is not a traditional systematic review or that avoids the use of effect sizes then it is almost certainly worse: subject to more threats, errors and distortions than the process you are uncomfortable with.

But because your new approach has never been done or advocated, it hasn’t yet been subjected to the same level of criticism.

In other words, to adapt Churchill’s famous quotation about democracy, systematic review based on effect sizes is probably the worst possible way to summarise what we know about the impact of interventions, apart from all the other ways that have been tried.

It isn’t perfect; we do need to understand the limitations; ideally, we need better studies and better reviews.

But given where we are, it’s the best we have.

By Rob Coe Since I became a researcher in the late 1990s, I have been an advocate of using effect size and meta-analysis for summarising and...

Should we be using systematic reviews and meta-analyses as teachers and school leaders to support the decisions we make, or is that a luxury? How do...

Before I trained as a teacher, I worked as a researcher, investigating the effect of phytoplankton processes in the ocean. It appeared that in...