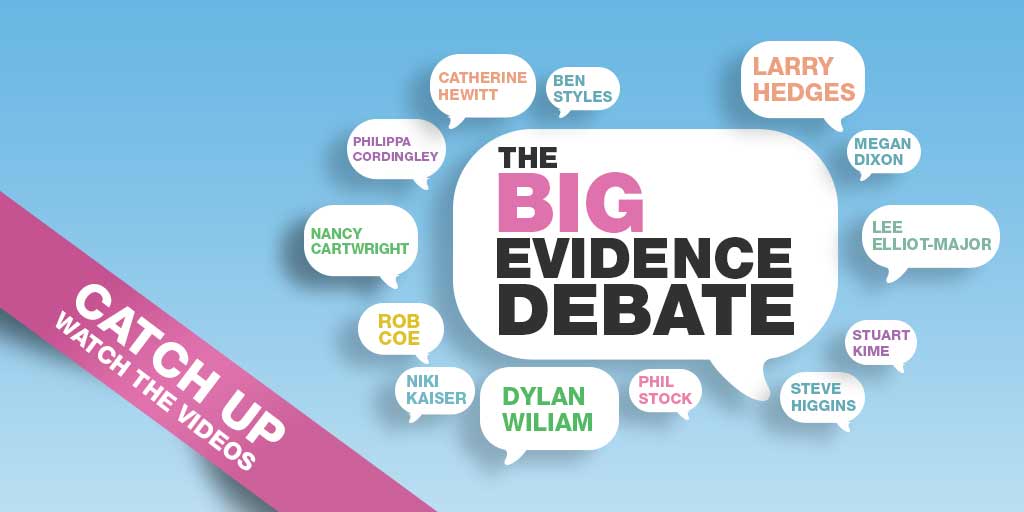

The Big Evidence Debate – Catch Up

On Tuesday 4th June 2019 we held the first ever Big Evidence Debate. Leading educational experts Dylan Wiliam and Larry Hedges gave fascinating...

Login | Support | Contact us

Tim Oates : Sep 4, 2019 1:45:00 PM

4 min read

The term ‘evidence-based policy’ rose to particular prominence in the early years of the New Labour administration, following the 1997 general election. At that time, the Standards Unit in the Department for Education commissioned research reviews, convened meetings of leading researchers to discuss key issues, and supported the formation of an equivalent to the medical Conchrane Collaboration – synthesising evidence from research which met certain criteria of method and integrity. The Economics and Social Research Council initiated a more strategic and issues-focused process of commissioning research.

The legacy of this time is important; educational journalists remain interested in the outcomes of research projects and programs, politicians do strive to formulate ‘evidence-informed’ policy, and key bodies such as the Education Endowment Foundation and Education DataLab apply high standards to the execution of research and the determination of recommendations for action. Publications such as TES and SchoolsWeek play a key role in pushing high quality research to the fore.

But it should not be forgotten that preceding 1997, educational reform and development in England has enjoyed a fine tradition of proceeding through wide formal consultation, scrutiny by Parliament and royal commissions, formation of policy through green papers and following white papers. All supported by a highly productive research community.

By 2010, the Review of the National Curriculum drew heavily on systematic transnational comparisons, implemented recommendations on ‘oracy in every subject’ from leading research programs, and used heavily research-derived principles (such as Reynolds’ and Farrell’s ‘fewer things in greater depth’ in Primary education) to drive decisions over structure and content.

This is not to say that judgement does not play a part in effective policy-making, or that research provides an answer to every pressing question of policy and practice. For example, we can determine with precision just how many – or rather how few – girls study Physics at A level (8384 girls, representing 22.2pc of the full cohort of 37,765 source IOP). But it is far more complex and demanding to determine the exact nexus of causes for this state of affairs, and more demanding again to put in place effective remedy.

As a nation we now have tremendous opportunity for increasing the role of sound evidence in policy and practice. We have excellent compilation of accurate data on attainment at 16 and 18, and the National Pupil Database now provides a remarkable platform for looking at patterns of attainment and progression, following people from entry to school and beyond, up to their point of entry to employment. With this, we have a sense of the performance of schools, of groups, of individuals, of localities and regions. This gives us the facility to monitor the effectiveness of new policy – and act in the light of knowledge, not just push forward strategy in the dark.

I sense a solid and enduring commitment to evidence-based policy in England. But there are some threats. Research itself must be well-designed, and linked to pressing issues. And I detect loud, misleading messaging about ‘kids don’t need to remember anything more’, or naïve oppositions such as knowledge versus skills, or teacher directed learning versus individualised instruction – all false oppositions which can distract from what the evidence quietly states.

And the worry about some of the naïve futurology which floats around policy circles and surfaces at conferences and in ‘rallying cry’ speeches is that not only does it have a very poor evidence-base, it also falls into the category of ‘manufactured anxiety’. The speeches and statements which focus on an ‘uncertain, threatening future’ frequently aim to induce anxiety and fear in the audience, and thus enhance the authority of the actions being endorsed by the speaker. ‘The future’s uncertain…so listen to me, and do what I recommend’.

The same syndrome affects some presentations of transnational comparisons: ‘…the Asian nations are improving so very fast…we are not, so we must be worried about this, so do as I am recommending…’. There are various problems with this approach – an approach adopted either deliberately or unconsciously – ranging from the ethical (arousing fear of others in order to induce compliance) to the technical (what Singapore is doing may or may not constitute any threat to other nations’ economic and social activity).

Two technical errors in this approach are serious ones. Firstly, of course the future is uncertain, it’s the future. But the future is capable of being shaped by human agency. The ‘be afraid, very afraid’ position tends to understate our capacity for effective action. Increased sophistication in evidence-based public policy diminishes disruption and adverse effects created by unmanaged social and economic processes. Events such as volcanic eruptions are not amenable to human action beyond the mitigation provided by better warning systems. By contrast, educational and social inequality are. Well-framed policy and action shapes the future rather than regarding it as inevitable.

Secondly, such arguments frequently misrepresent the complexity and real trajectory of other nations. Finland, the country so frequently regarded as representing the pinnacle of educational prowess, was in fact in decline when it came top on the key measures in the first PISA survey in 2000. Finland is an exceptionally interesting country, but for what it was doing prior to and when it rapidly improved – and that was during the 1970s and 80s. Singapore, which should be hugely respected for its extraordinary improvement in attainment and equity during the 70s 80s and 90s is, like many nations, grappling with rising pupil stress and issues of narrow focus on exam performance.

We need less naïve futurology, and more sophisticated policy formation which draws on well-designed and executed research. Fortunately, in England there are distinct signs for optimism - I think we have a proud tradition of using evidence and an increasing appetite for using it to shape our policy, and thus create, not be battered by our future.

Tim Oates joined Cambridge Assessment in May 2006 to spearhead the rapidly growing Assessment Research and Development division. His work has included advising on a pan-European 8-level qualifications framework and chairing the UK government’s national curriculum review. Tim was awarded CBE in the 2015 New Year's Honours for services to education.

Catch up on the presentations from The Big Evidence Debate

On Tuesday 4th June 2019 we held the first ever Big Evidence Debate. Leading educational experts Dylan Wiliam and Larry Hedges gave fascinating...

by Professor Robert Coe We’ve all done it: observed another teacher’s lesson and made a judgement about how effective the teaching was. Instinctively...

To test, or not to test? That is the question which provokes one of the most keenly fought debates in education policy, and which can lead to soul...