What is Worth Reading for Teachers Interested in Research?

I give a fair number of talks to groups of teachers and school leaders on the subject of connecting educational research with their practice. Often I...

Login | Support | Contact us

Lee Elliot-Major : Jun 6, 2019 1:39:00 PM

3 min read

As a news editor, I developed my own 50% rule: reporters should spend as much time writing their stories as getting the stories in the first place. Journalists often race back into the newsroom with great tales to tell. But they don't work hard enough on their copy to convince readers to give up valuable time to digest what they have written. The central message isn't quite clear. Headlines are buried away. Editors, to their eternal frustration, always run out of time to do the articles justice.

I’ve spent a lifetime trying to translate the complex jargon of academe into accessible language. Daniel Kahneman’s wonderful book Thinking Fast and Slow confirmed my instincts: we are hardwired to understand narratives and bamboozled by the simplest of statistics.1

Communicating research is like moving from one world to another.

We are also prey to the burden of knowledge bias: assuming others will understand our areas of expertise, and believing our uncovered truths are self-evident. What you communicate is as important as the content you create.

And so it is with the synthesis of summaries of education studies. How the results are disseminated is just as critical as the accuracy of the summaries themselves. When we debate the weaknesses of meta-analysis we can only do so by considering what they are intended for.

This balancing act between communication and content was at the heart of our work developing the first incarnation of the Education Endowment Foundation Teaching and Learning Toolkit.2 This guide, offering best bets for learning based on 1000s of studies, is now used by two-thirds of school leaders across England and has been replicated across the world.3 The toolkit confirms what every good teacher knows: the most impactful approaches in schools relate to the interaction between teacher and pupils in the classroom.

The toolkit’s success has been down as much to careful presentation as the detailed calculations that underpin its conclusions. We made brave calls to translate effect sizes, the comparative impacts of interventions, from standard deviations into the language of the classroom: extra months gained by pupils during an academic year.4 (I’ve always contended that if you present anything in standard deviations you immediately lose 3 standard deviations of the population!)

The toolkit estimates are only guides for teachers based on the limited research on which they stand. The impact on children varies more within each toolkit strand than it does between strands. It's not choosing to do peer tutoring that matters but how well you do it. Feedback in the classroom, for example, delivered well, yields on average higher learning gains compared with most interventions. But feedback can also harm learning. The inherent uncertainties of applying evidence in the classroom have been confirmed by randomized controlled trials commissioned by the Education Endowment Foundation. Three-quarters of approaches trialled are no better than ‘teaching as usual' in other schools.

The dilemma has been how to ensure these nuances don’t get lost in the headlines.

“Setting and streaming? NO. Teaching assistants? NO,” declared a BBC article about the toolkit’s findings as the Government launched its What Works initiative.5 The implication was that the complex activity of teaching could somehow be completely dismantled into simple scientific instructions.

As a former editor, I grimaced when I saw those headlines. Research can only tell us what has worked on average in the past for some pupils, not what will work in the future for other pupils. Flawed evidence is the best we’ve got but it must be used with care. Carefully couched in caveats, best bets for learning grounded on the balance of evidence are justified. Crude teacher diktats of ‘what works’ are not.

1 Kahneman, D. 2011. Thinking Fast and Slow. London: Allen Lane.

2 https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/evidence-summaries/teaching-learning-toolkit

3 https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Survey-evidence-from-pupils-parents-and-school-leaders.pdf

4 See technical notes for our assumptions converting effect sizes into months of learning

5 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-30210514?SThisFB

Lee Elliot Major is Britain’s first Professor of Social Mobility. Appointed by the University of Exeter to be a global leader in the field, his work is dedicated to improving the prospects of disadvantaged young people.

He was formerly Chief Executive of the Sutton Trust the UK’s leading social mobility foundation. Lee is a founding trustee of the Education Endowment Foundation which has carried out 100s of major research trials in England’s schools. He is a senior visiting fellow at the LSE’s International Inequalities Institute and an Honorary Professor at the UCL Institute of Education. He commissioned and co-authored the Sutton Trust-EEF toolkit, a guide used by 100,000s of school leaders and replicated across the world.

Niki Kaiser’s Where is the value in meta-analysis?

Megan Dixon’s Systematic reviews and meta-analyses – what’s all the fuss?

Phil Stock’s Meta-analyses and the making of an evidence-informed profession

I give a fair number of talks to groups of teachers and school leaders on the subject of connecting educational research with their practice. Often I...

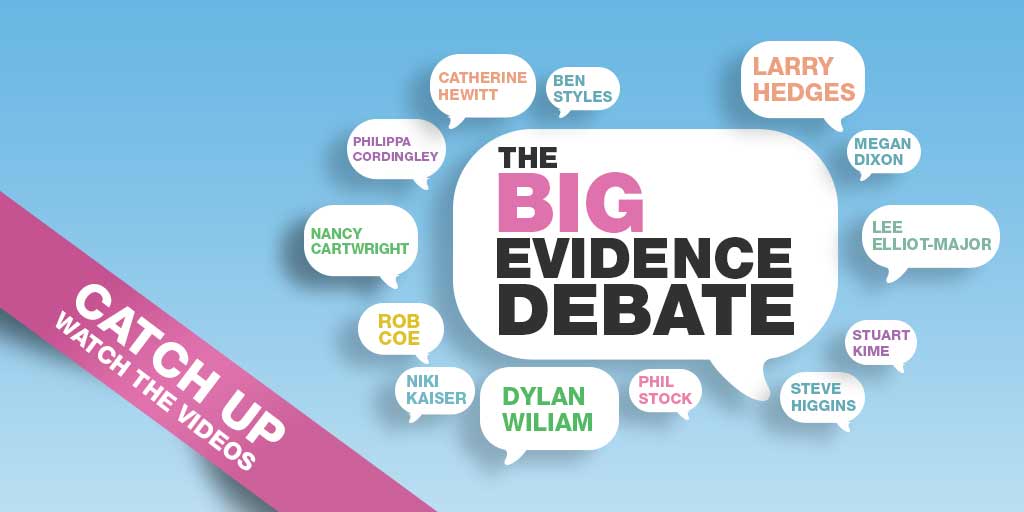

On Tuesday 4th June 2019 we held the first ever Big Evidence Debate. Leading educational experts Dylan Wiliam and Larry Hedges gave fascinating...

Meta-analysis involves the aggregation of data from existing studies that share key features, in order to create a summary that reflects all the...